A synthesis paper of the Permafrost Climate Feedback just came out in Nature this week (paywalled, but it’s here). Field buddy Jorien is a co-author, so congrats to her! I’m going to take this opportunity, then, to wax eloquent about permafrost and climate. Plus the paper has some cool figures that I think everyone should see.

Permafrost is any ground that is below freezing (0°C) for two or more years. Permafrost can be icy – some yedoma soils contain up to 80% ice – but often it is just cold. The easiest way to piss off an Arctic scientist – say permafrost is melting. Permafrost thaws, it doesn’t melt (see the update at the bottom of the article. We get testy).

Often, permafrost has been frozen not just for two years, but for thousands or tens of thousands of years. Some permafrost has survived as much as 740,000 years. It acts like a giant freezer, storing animal bones and mammoth mummies. But, even more importantly, permafrost regions store as much as 1670 billion tons of organic carbon. To put this in perspective, that is more than twice as much carbon currently in the atmosphere or in terrestrial vegetation. That carbon has been locked away for millennia, but the freezer is beginning to thaw. As permafrost warms, the preserved soil carbon can be decomposed, releasing carbon dioxide and methane – both powerful greenhouse gases.

We, as a scientific community, have been trying to quantify this process. How much carbon, exactly, is stored in permafrost? What portion of the frozen organic carbon can be decomposed into greenhouse gases? How much of the permafrost will actually thaw over the next century? What timescale will this process occur over – abruptly or over decades? Where will the carbon decompose – in the soils, or in streams, lakes, rivers or estuaries? We still don’t know all of this, but we have some pretty good estimates.

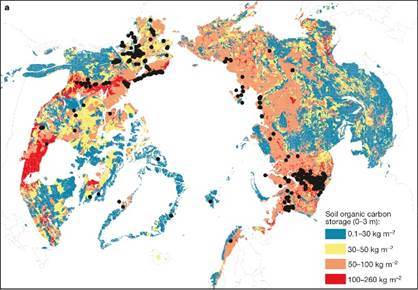

First, as you might have guessed, we are becoming more confident about how much carbon is actually in the permafrost soils. Some of the more remote areas in Siberia and the High Canadian Arctic still need more measurements, but the Permafrost Carbon Network database now contains many soil cores from all over the Arctic, including deeper soil samples that used to be rarely collected. Subsea permafrost is the biggest unknown. This is permafrost that formed during the last ice age, when sea levels were much lower, and has since been inundated by rising oceans. Still, estimates for permafrost carbon are converging around 1300 – 1700 Pg C (units are petagrams, or billions of tons).

If permafrost does thaw, what percentage of the carbon contained can actually be mineralized, turned into CO2 or CH4? This is a complicated question, and one of the most important ones. Elberling et al. (2013, paywalled) did a great experiment where they incubated permafrost soil for 12 years to see how much carbon was lost. Twelve years! I was nine when they started that project (it also took them, like, 5 years to publish after completing the experiment because writing/publishing is ridiculous – another rant for another time).

Anyway, as much as 75% of the carbon was mineralized – turned, by microbes, into CO2. Not all soils are created equal, though. A friend did some experiments in Cherskii, Siberia and only a small percentage of the carbon was lost. Joanne was limited by her time in the field, so a longer incubation could have different results. Other factors matter too – exposure to sunlight can break down organic molecules, releasing CO2 even faster. The ratio of nitrogen to carbon (it’s juiciness, as one of my committee members would say) matters. All in all, the decomposability or lability of organic carbon varies widely.

Still, we can combine what we do know of the lability with warming projections, to try and estimate how much carbon will be released from permafrost over the next century. These models still need work, but there seems to be some convergence between multiple methods. Or, we’re not sure, but people using the different data and different methods seem to be coming to about the same answer, so let’s go with that for now. Until we can get better data and better methods.

Including just gradual permafrost thaw (there’s also abrupt thaw, but I’ll save that for a different post), we seem to be facing 5 – 15 % of permafrost carbon loss during this century. Again, putting this in perspective: land use change (deforestation, etc) released about 0.9 Pg C per year from 2003 to 2012 (as said in Schuur et al). If that held constant over the century (unlikely, but just for arguments sake), that means human-driven land use change would emit about 90 Pg C by 2100. Loosing 10% of permafrost carbon would be about 130-160 Pg over a century.

Of course, that is a VERY back of the envelope calculation, and permafrost carbon would only be a fraction of the fossil fuel emissions (9.9 Pg in 2013, and it increases every year unless policies change drastically soon). Still, it is useful to think about just how important the permafrost climate feedback could be. And none of the current climate projection models include the permafrost climate feedback – yet they all include land use change.

What does this all mean? The permafrost climate feedback will exacerbate climate change. Warming climate thaws permafrost. Permafrost releases additional greenhouse gases. Greenhouse gases warm the atmosphere more. More permafrost thaws. This loop, or positive climate feedback, needs to be included in our decision making. There are still unanswered questions about permafrost. But we know that this carbon pool is vulnerable. And we know that it will contribute to global climate change.